Contact Beth Northrop

ejnorth123 AT juno.com

![]()

Leeds,

San Francisco, Southport, Connecticut

This

is still a work in progress...

RICHARD WEBSTER born in 1692 or 1696 Note: The claims below are entirely based on the IGI. Whilst thought to be the right lineage down to Charles Benjamin Webster (1820-1896), the facts are not proven from source parish records. RICHARD WEBSTER is the father of Samuel Webster, my ancestor, born in Spofforth in the West Riding of Yorkshire. His date of birth is uncertain because a search of the I.G.I reveals two Richard Websters born around the same time. They are;

Both were born in the reign of William and Mary and a few years before the Union of England and Scotland. There were a number of Websters living in this small village so the likelihood is that the two men were cousins. A further I.G.I search reveals that the two men were married as follows;

Son Samuel and all his siblings were born before 1734, therefore correctly identifying Richard with Sarah Tidewell as my line. Richard and Sarah had seven children, including Samuel, my ancestor:

The first Samuel died within the year and the parents used the name again, not an uncommon occurrence in days when infantile death was commonplace. Certainly the Websters kept the Rector busy with christenings, weddings and funerals! SPOFFORTH CHURCH SPOFFORTH RECTORY The Webster family were certainly domiciled in Spofforth over a number of generations and searches show a number of related families. Spofforth with Stockeld is a lovely Yorkshire village, situated at the crossroads to: Wetherby, 3 miles; Knaresborough 4 miles and Harrogate, 5 miles. Spofforth has a ruined castle, the former home of the Percy family who lived here from Norman times until Henry Percy purchased the barony of Alnwick in Northumberland, (becoming The Duke of Northumberland), and where his successors remain today. Henry left Spofforth Castle to fall into disrepair and, with the help of the Civil War, it became the ruin it is today. |

|

| ??? maybe James Webster 1687 Spofforth guess ??? |

||||||||||

| ??? Maybe Richard Webster1711 Spofforth guess??? |

||||||||||

| Samuel Webster year 1729 & Mary Wood (prob) Spofforth LI NK |

Spofforth | |||||||||

| William Webster, 1778 -

1848 & Matilda ? 1782- 1852 LINK |

Spofforth(1778) Allerton Mauleverer(1803 check) Killinghall(~1820) Bowling, Bradford Horton (Isaac) |

From: Paul W Sent: Saturday, December 31, 2011 11:26 AM To: Colin ; Beth

Hello folks , I have had a look at the records recently added to Ancestry. There is no sign yet of a marriage of William Webster to Matilda c 1803 or Births / Baptisms for William and Benjamin born Bradford c 1845/47 However there are several interesting things . George Webster b 12 Apr 1852 , Bap 6 Jan 1853 Bradford ; son of Benjamin and Eliza |

||||||||

| Charles Benjamin Webster 1820 -1896 & Eliza Ann Parker 1823 - 1900 LINK |

Killinghall(1820) Bowling, Bradford (b4 1841) |

|||||||||

| Benjamin Parker Webster 1843 - 2/11/1908 Bpt & Margaret Longhorn Calam 7/14/1846 - 3/11/1923 Lakeview LINK |

Bowling, Bradford (b4 1841) | |||||||||

| Earl P. Edward Edgar Parker Webster, b. 10/ 23/1867 West Leeds- d. 12/13/1952 age 85 Bpt | Edward

Parker b. ? - d. ? Edgar Ferdinand b. 1/21/1893 - d. 6/1980 Monroe, CT age 87 , Mrs. E. F. 64 Montgomery Street Bridal Shower March 19, 1920 for Lillian M. Webster, her sister-in-law Lillian Margaret b. ? - d. ? married Willard |

|||||||||

| Mary Florence Webster b. 11/4/1869 CT - d. 11/5/1951 Bpt., CT age 82 (married cousin see Benjamin C. for two children) | ||||||||||

| Harry Calam Webster b. 1/22/1871 CT m. Mame (Laubshier/Leaman) .kids Ethel Elizabeth "Ethel" /Margaret Elizabeth "Nan" another date for birth 10/14/1877 d.2/17 1961 | Ethel

Webster b.? Nan Webster b. ? |

|||||||||

| Ross Benjamin Webster b. 11/28/1878 CT m. Carrie Ballard (son who died early fm census?) | ||||||||||

| Aubren Webster b 1879 ? CT from census, but no other mention of Aubren | ||||||||||

| William

Webster b.1/13/1848 or 1846 or 1847 in Bowling Bradford LINK |

Bowling, Bradford (b4 1841) | |||||||||

| d/o Holmes | Mary Ann Webster b 12/11/1872 Location? is MA Holmes census b. 1873 actually MA Webster? OR b. 1867?? | |||||||||

| c/o Ellen Francis Mulholland Gallagher (Mulholland or Gallagher late husband?) b. 1846- or 1848(census date) Boston, MA Met in Boston? had child Harriet by previous husband? Parents both from Ireland married in SF b 10/9/1845 Boston MA d. 3/12/13 Berkeley 1826 Prince Street. age 67, buried St Mary's Cemetary says father Mr. Holland (Ireland) not Mulholland ? Mother's maiden name not known (Ireland) from death cert. | William

Lester Webster b. 1876 born SF August 1st 1899 Parish Church of Armley ( St Bartholomews ) |

Wilma Webster married to Beverly

Brace last known address 1161 Trinity Drive Menlo Park, CA Eunice Webster |

||||||||

| Lilly Mae Webster maybe Sheffield b. about 1877 married to John Thomas Brammer 1922 Paul b. 1874 | ||||||||||

| Benjamin

C. Webster b. 2/9/1878 SF d 8/2/63 age 85. Oaklawn

Cemetary, Fairfield, CT When young called Bennie. Development Engineer

Mechanical & Electrical LINK |

Benjamin

Chester Webster, Jr. b. 1905 Jr. married Ruth about 1942? SHibbard

d.5/29/1979 Margaret Gwendolyn Webster b. 1/7/12 Berkeley, CA d. 3/?/1990 m. 5/8/1948 Alvin Jennnings Northrop |

|||||||||

| Marian Mary Cecilia Webster Black Green ( (Minnie) F. Webster b. 2/24/1885 Leeds d. 9/14/1945 Millbrae, CA Paul b. 1883 | Nancy Ellen Black Green b 9/16/1939 SF married L'Heureux | |||||||||

| Edington Henry Webster born Armley 1884 registered Leeds UK (Paul) maybe died Nov 19th ?? (Lucy)"Eddie" LINK |

||||||||||

| Mabel Ellen Webster b. ? d. June 16 married William Zazzi CA | ||||||||||

| d/o her previous marriage | Hattie Harriet Gallagher Webster b. about 1860 Died April 25th she may be the Gallagher by previous marriage perhaps was at prince st when father William Died in 1925. listed as Hattie Gallagher (no Webster) d. 10/9/29 Prince St Berkeley 1903 Hattie on passage with Wm, Mrs, etc. another Ellis Island November 6, 1910 from liverpool age 43, says to 100 State Street Chicago but there is another entry on manifest for Elsworth Avenue, Berkeley, CA also February 27, 1922 Hattie M. Webster age 54 departed San Juan Puerto Rico says born kendalville iowa March 12, 1867? to 4520 Ellis Avenue, Chicago, IL | |||||||||

| Ellen Webster O'Leary high position in girl scouts visited in southport when I was small | ||||||||||

| ? of 13 | ||||||||||

| ? of 13 | ||||||||||

| ? of 13 | ||||||||||

| ? of 13 | ||||||||||

| ? Mary Webster b. 1871 - d. ? last UK census shown 1881 | ||||||||||

| ? Emma Webster b. 1878 - d. ? last UK census shown 1881 | ||||||||||

| Isaac Webster, born 30 March 1804 Christened 4 Sept 1804 (Minister: James Neale) George Webster ‘’ 13 January 1807 ‘’ 9 Oct 1807 William Webster‘’ 7 January 1808 ‘’ 9 Jan 1809 Matilda Lydia ‘’ 14 October 1809 ‘’ 28 May 1810 Frances Elizabeth ‘’ 19 May 1811 ‘’ 31 May 1811 Caroline ‘’ 12 February 1813 ‘’ 15 Feb 1813 Sarah (Joaca ?) ‘’ ‘’ 2 April 1815 |

||||||||||

The bishop’s transcript (seen at the West It is interesting that Horatio Gratton, an uncle William had by this time, moved to pastures |

||||||||||

Then came the move into the industrialised William Webster, father. Age 65, a Wool Buyer

Their son George, 35, was also married Son, Charles Benjamin, was also working Their son Isaac was living in nearby |

||||||||||

It has been difficult to ascertain the date of It is interesting that son, Charles Matilda died on 6 July 1852 at MATILDA CERT

END NEW CHARLES BENJAMIN WEBSTER |

||||||||||

The Bishop’s Transcripts also Nearly all references to Charles Benjamin was born into a time of Mary and Catherine Ingleby |

||||||||||

| The world into which Benjamin was born was pre steam, gas, electricity and any motive power: aeroplanes would have been science fiction! In the year he was born, George the 3rd. died and George 4th. and Queen Caroline succeeded to the throne with the Earl of Liverpool as Prime Minister. Not for another 12 years did the Factories Acts ban children under the age of 9 working in factories and limiting the working hours of children between the ages of 9 and 13 to 8 hours a day! I do not have pictures of working people but these pictures of the upper classes, to whom they answered, show the dress of 1820. |

||||||||||

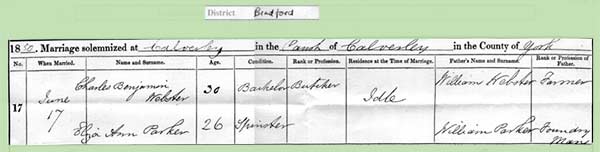

Charles Benjamin Webster married The couple were married on 17th June 1850 at Calverley, near Leeds. By the census of 1851 they were living in their own home at 73 Wakefield Road, Bradford. Benjamin was 31 and still working as a butcher: Eliza was 28 and the couple had 2 children: • Benjamin Webster jnr., aged 7 and born in Bowling, Bradford |

||||||||||

| Spofforth now youtube link Open meadows, secluded woods, ponds and hedgerows....under the watchful eyes of the local Red Kites soaring high above. The first nips of frost nibble as the Green man casts his protective winter cloak over the land.  |

||||||||||

|

Click for larger image

See Forest boundry below

1789 Book The History of the castle, town and forest of Knaresborough, with Harrogate, and its medicinal waters. Including an account of the most remarkable places in the neighbourhood.

(searchable full view, but search limited by old spellings and typeface -- Spofforth is Spofford)

Google Books version may be a little easier to read

The totality of the Manor was known as the Honour of Knaresborough and comprised three parts – the Forest, the Borough or Town, and the Forest Liberty. In medieval times a Forest was not simply an extensive expanse of wooded area but included clearings and settlements and was associated with hunting. The Forest of Knaresborough was located west and south-west of the town and covered about 100,000 acres, stretching twenty miles from east to west. The inhabitants of its settlements were occupied in farming, fishing, charcoal burning, and iron smelting. The Forest Liberty was an area of farmland to the north of the town where its dozen villages occupied a fairly flat and easily cultivated landscape. We now begin to see the town developing. The earliest recording for the parish church is in 1114 in the Coucher Book of Nostell Priory as “the Church of Cnaresburgh” and we can today see remains from this time, particularly in St John’s which has outlines of Norman windows and a typical chevron patterned string course. The first documentary evidence for the castle occurs in 1130 in an account of works carried out by Henry I, when Knaresborough is again described as “Chenardesburg”. When the direct line of descent of the Stuteville lords of the manor was interrupted, King John contrived to take over the Honour for himself (1204/1205) by the levy of a fine. The king was then able to collect various revenues associated with rents, harvests, court proceedings etc. In 1211 the revenue came to £318, 19s 3d (Early Yorkshire Charters). In the same year his outgoings included “work on the castle of “Cnarreburc” and on the ditch and houses thereof for 2 years £119, 18s. 8d.”; also “in work on a new mill, improvement of fulling mills and repair of the mill-pools of Knaresborough and Boroughbridge £15, 8s. 2d” (Early Yorkshire Charters). He was one of several royal visitors who enjoyed hunting in the forest. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~ The Early CastleLike all castles, Knaresborough served as a focus for the surrounding community: a refuge in times of danger and a centre for government and judicial administration. Long after the castle’s military significance had diminished, it continued to function as a centre for justice, administering the Honour of Knaresborough. Even after the castle was ordered to be dismantled by the Parliamentarians, the townspeople of Knaresborough managed to successfully petition the government to allow them to preserve the King’s Tower and to use it as a prison. Like all castles, Knaresborough served as a focus for the surrounding community: a refuge in times of danger and a centre for government and judicial administration. Long after the castle’s military significance had diminished, it continued to function as a centre for justice, administering the Honour of Knaresborough. Even after the castle was ordered to be dismantled by the Parliamentarians, the townspeople of Knaresborough managed to successfully petition the government to allow them to preserve the King’s Tower and to use it as a prison. Very little is known about the early history of Knaresborough, and the origins of the castle are equally obscure. The first reference to the town is from 1086 in the Domesday Book, and although we know that much of ‘Chednaresburg’ was in the possession of the King, there is no mention of the castle. The name Chednaresburg implies a fortification, and is the only tantalising glimpse of a predecessor to the medieval castle. ‘Burg’ is an Anglo-Saxon word for a defended enclosure, and suggests that Knaresborough may have had some form of early defensive structure. This would most likely have taken the form of a bank and ditch surrounding the town, and would not refer to the presence of a castle. The earliest castle at Knaresborough was established after the Norman conquest, predating the standing fourteenth century remains by nearly 200 years. Throughout its long history, the castle has been in royal control or held directly from the Crown. Its fortunes have risen and fallen with the history of the English Monarchy. The first documented reference to a castle at Knaresborough is from the Pipe Rolls of 1129-1130, which make reference to £11 spent by Eustace fitz John for the King’s works at Knaresborough. In 1170, when Hugh de Moreville held the castle, he and his followers took refuge there after they had murdered Thomas a Beckett in Canterbury. King JohnKing John took a particular interest in Knaresborough and he spent £1,290 on works at the castle, including the excavation or enlargement of the moat. The remains of this great dry ditch can still be seen around the southern and northern halves of the castle, and this is the earliest remaining visible construction. King John visited often during his reign, residing here while hunting in the Forest of Knaresborough. The vast area covered by the medieval Forest of Knaresborough would have provided excellent grounds for this pastime, and the royal privileges in the Forest were carefully guarded. King John maintained Knaresborough Castle as one of his administrative strongholds in the North. He is reputed to have spent more money on the castles at Knaresborough and Scarborough than on any others in the country. Knaresborough repaid his patronage, and was held for the Crown during the Baron’s Revolt in 1215-16. The lack of visible remains from this period, apart from the moat, and possibly the lowest storey in the Old Courthouse, presents a misleading picture of its importance at this time. The money spent on the castle and the people who spent time there are clear signs of its important status in the affairs of the country. The Edwardian CastleEdward IIn the early 14th century King Edward I turned his attention from his successful Welsh campaigns and looked toward the North. He began a programme of modernisation at Knaresborough Castle, and made repairs to buildings referred to in court records as the ‘White tower, the great hall, the great chamber, the great chapel, the chapel of St. Thomas and the great gate’. These historical references are the only record we have which can give us a picture of the castle at this period. From the brief glimpse they give us, we know that Knaresborough Castle consisted of a substantial range of buildings by the 14th century. All that survives from that period now are the twin towers of the East Gate and fragments of the curtain wall. Edward IIWhen Edward of Caernarvon succeeded his father Edward I to become King of England, the country lost a strong ruler to a weaker man, who was influenced by unpopular favourites. Piers Gaveston was the first of these men to gain Edward’s favour, and in 1307, Edward II granted the Honour and Castle of Knaresborough to Gaveston. In reality the estate remained in the King’s control, and a substantial amount of money from the royal purse was spent on the Castle. Piers Gaveston was extremely unpopular amongst the powerful barons, who felt he exercised undue influence over the King. In 1311, under pressure from the barons, he was banished, but was later re-admitted into the country and the King’s favour. In 1312, Gaveston was besieged at Scarborough Castle. During the siege, Edward remained at Knaresborough Castle, to be close at hand. Gaveston surrendered and was eventually beheaded. Edward II’s reign was marked by continuing internal friction amongst powerful factions, and ever increasing raids by the Scots into northern England. This general unrest led to rebellion and on 5 October in 1317, Knaresborough Castle was seized by supporters of the Earl of Lancaster, and held against the King. The Constable spent ,£55 to mount an attack to retake his own castle, and used a siege engine to breach the curtain wall and recapture it three months later. In 1318 the raiding Scots penetrated as far south as Knaresborough. Much of the town including the church and priory were devastated by these raids, with the castle as the only point of refuge in the town. The powerful aristocracy were soon in a state of complete rebellion, led by the King’s own wife, Queen Isabella. In 1327 they deposed Edward II and accepted his son as King Edward III. It was an age when the monarch needed to be strong and forceful in order to reign successfully. Edward I had been a strong, determined man who ruled with great control. His son could not have been more unlike in character. Where his father had subdued Wales, Edward II suffered humiliating defeats at the hands of the Scots. After losing the throne, Edward II was imprisoned and eventually barbarously murdered. Edward IIIIn 1331, Edward III’s wife Queen Philippa received the Honour and Castle of Knaresborough as part of her marriage settlement. It was while in her possession that Knaresborough Castle became firmly established not only as a royal possession, but as a royal residence in the truest sense. Previous monarchs had used the castle to consolidate their power in the North, but Queen Philippa spent many summers in residence at Knaresborough Castle, her young family with her. During this period, up until her death in 1369, much of the summer court season would have revolved around Knaresborough Castle, and the elegant King’s Tower and dramatic view from the cliff would have been familiar scenes to members of the Royal Court. Lancastrians & TudorsDuchy of LancasterIt may have been memories from his childhood spent in Knaresborough that encouraged John of Gaunt, in 1372, to give up his properties in Richmond for the Honour and Castle of Knaresborough and the Honour of Tickhill. As Duke of Lancaster, John of Gaunt had a large inheritance including many castles of great importance. Knaresborough from that time onwards was joined to these estates and belonged to the Duchy of Lancaster. Upon John of Gaunt’s death in 1399, King Richard II confiscated the Lancastrian estates as the property of the Crown, disinheriting Henry Bolingbroke, John of Gaunt’s son and heir. Henry returned to claim his inheritance, landing at Ravenspur, and travelling to receive support from his Castles at Pickering, Knaresborough and Pontefract This confrontation eventually led to the downfall of King Richard II, who was deposed and imprisoned. He spent a night as prisoner in Knaresborough Castle, most likely in the King’s Tower, before he was taken to Pontefract, where he was murdered. Henry Bolingbroke’s ascendance to the throne as King Henry IV brought the lands of the Duchy of Lancaster directly under the control of the Crown, and Knaresborough was a royal castle once again. The Late Medieval CastleAlthough the accession of Henry IV brought the Lancastrian inheritance under control of the Crown, Knaresborough Castle no longer played an important role in national affairs. The castle continued to serve a crucial function in regional administration, and the manor courts were still held here. The history of the castle during this time until the Civil War is fairly obscure, illuminated only by occasional references which show it was kept in good repair. It remained directly in control of the Crown throughout this period, except from 1422 to 1437 when it formed part of Queen Catherine’s dower, when her husband King Henry V died. The Tudor CastleCastles had largely lost their defensive significance by the Tudor period, and new tastes were leading to the construction of fortified stately homes rather than old-fashioned and less comfortable castles. However, many castles were maintained and modernised, and in both 1538 and 1561 surveys were undertaken which showed Knaresborough Castle to be in a state of disrepair, but not decay. The timber and leadwork throughout the castle needed to be replaced, and most of the timber buildings were beyond repair. The stonework was essentially in sound condition, and was considered to be easily made defensible again. By 1600 the upper storey of the Courthouse was built, and court cases from the Forest and Liberty of Knaresborough were tried here. Whether the repairs identified in the earlier surveys were undertaken is not known for certain, but by the Civil War, the castle was still able to be defended. Civil War to Modern DayThe Civil WarKnaresborough Castle supported the Royalist Cause during the Civil War, but in 1644 the Parliamentarians were gaining control in Yorkshire. After the battle of Marston Moor in July 1644, the castle was besieged, and finally surrendered when cannon breached the wall on December 20. In 1646 Parliament ordered the castle to be rendered untenable, and by 1648 demolition had commenced. Nearly the entire circuit of the curtain wall was destroyed, as were all the buildings in the grounds, except the Courthouse. The King’s Tower was in the process of demolition when the townspeople petitioned Parliament to allow them to maintain it as a prison. Demolition was halted and the Tower was left standing. The King’s Tower and Courthouse continued to serve as prison and courthouse for some time. The Modern CastleIn the early 20th century, a bowling green and tennis courts transformed the role of the castle in the town, creating a leisure area for local residents, and relegating the structures of the castle to a secondary, almost superfluous role. The putting green now occupies the area where the tennis courts used to be. A war memorial commemorates the many local residents who gave their lives in the defence of their country in the First and Second World Wars. The Courthouse is now a museum which provides an explanation and interpretation of the history of the town, and which still contains furniture from the original Tudor courtroom. The castle now stands as a monument to Knaresborough’s history, and as a centre for interpretation and understanding of that past. The 20th century has seen a renewal of interest in our historic monuments; in their preservation and interpretation, and in their value as integral elements in our modern landscape. The standing buildings and fragments of wall within the castle grounds provide a glimpse not only into the activities of the past which led to their construction and use, but also to the late activities of disuse and destruction. In their own unique way they stand as a permanent reflection of the changing values and attitudes of our society, from Medieval times to present day. ‘The King’s Chamber’, and it is believed that it was here that Richard II was imprisoned before being taken to Pontefract Castle Hugh de Morville was Constable of the Castle of Knaresborough and leader of the unfortunate group of four knights who took King Henry II at his word when he said “will nobody rid me of this turbulent priest”. On December 29th, 1170 they murdered Thomas Beckett, Archbishop of Canterbury, on the steps of the altar of his cathedral. The four knights first fled to Knaresborough, where legend has it that they were reviled even by the dogs of the town, although Hugh is also said to have built Hampsthwaite Church and dedicated it to the canonised priest as an act of penance. Rebels occupied the castle during Edward’s reign and the curtain wall was breached with a siege engine during its recapture. Later, Scots invaders burned much of the town, including the parish church. The church was restored by Queen Philippa, wife of Edward III, who had been granted “the Castle, Town, Forest and Honour of Knaresborough” as part of her marriage settlement in 1328. After her death the Honour was granted in 1372 by Edward to their youngest son, John of Gaunt (born in Ghent). He had already inherited the estates of his wife, Blanche of Lancaster, and was Duke of Lancaster and thus linked the Honour of Knaresborough with the Duchy of Lancashire and hence to the Lancastrian cause in the Wars of the Roses. King Richard II spent a night in Knaresborough Castle on his way to Pontefract Castle in 1399 where he was murdered. The various religious upheavals of the first half of the sixteenth century, during the reigns of Henry VIII, Mary and Elizabeth, affected the people of Knaresborough who were generally loyal to the Catholic faith. They were conservative in their religion and slow to accept new ideas, especially if imposed from above by a distant monarch. In addition, most of the local landowners and lords were of the Catholic faith. After the unsuccessful Rising of the North in 1569 services were still being secretly held but the Protestant religion gradually became established. In 1580 a great effort was made to suppress recusancy (the refusal to conform) and an Act of Parliament the following year made this a crime punishable by a fine of £5 a week. At this time the parish church became firmly established as the church of St John the Baptist, having previously sometimes been known as St. Mary’s (a more Catholic name)and the Parish Register was begun in 1561 with the recording of 41 baptisms, 12 marriages, and 21 burials in its first year. Thatched Manor Cottage at the bottom of Water Bag Bank (up which ponies carried bags of water from the river to the town) dates from this period. Effigies of the Slingsby family in the parish church are worthy of note and include the recumbent Francis Slingsby who died in 1600, cavalry officer to Henry VIII, with his wife lying on his right hand side as she was from a higher born status of the Percy family. Other notable tombs are those of Sir Henry Slingsby, executed under Cromwell in 1658, and Sir Charles Slingsby who drowned in 1869. The church also contains a fine late Jacobean font-cover. During the civil war Knaresborough was a Royalist stronghold. The castle remained loyal to King Charles but was taken by Cromwell’s soldiers, after a short siege, on December 20th, 1644. A popular story tells (see e.g. The Knaresborough Story) how a Mrs Whincup successfully led a group of people to plead with the commander for the life of a boy found taking food to his besieged father. The castle suffered little damage at this time but in 1648 was a victim of an Act of Parliament ordering the demolition, or “slighting”, of several Royalist castles. Sir Henry Slingsby, MP for Knaresborough, who had been expelled from the House of Commons for his Royalist tendencies in 1642, remained determined to restore the monarchy. He was arrested in 1654 and charged with high treason. Being found guilty, he was beheaded on Tower Hill on June 8th, 1658 and his headless body returned to Knaresborough for burial. The early 17th century saw the establishment of King James’s School in the town, its charter being granted in 1616, beginning a long tradition in the town emphasising the importance of education. Originally this was an all-boys school, endowed with £20 per year by Rev. Dr. Robert Challoner, who was born in Goldsborough, and boys from Knaresborough and Goldsborough were to be admitted free, with fee-paying scholars admitted at the discretion of the governors. By 1820, however, there had been no free scholars for over twenty years. The Charity School was established at the bottom of the High Street by Thomas Richardson in 1765. It was to accommodate “thirty boys and girls of the township of Knaresborough, and for putting them out to apprenticeship”. Several Sunday Schools provided elementary education for all denominations. It was in the latter half of the sixteenth century that Knaresborough’s reputation as a spa town began with its recommendation as a base for taking the newly discovered waters of Tewit Well. Many eminent travellers of the day, including Celia Fiennes (1697) and Daniel Defoe (1717) visited Knaresborough at a time when Harrogate was still only two small hamlets – Low and High Harrogate. Inns and hotels were being built in High Harrogate but the tradition at this time was to stay in Knaresborough and travel to the Harrogate area to take the waters. The textile industry has been associated with Knaresborough for centuries – records of 1211 mention mills. While the woollen market expanded in the sixteenth century to satisfy an increasing population and the quality of its cloth improved, interruptions to export caused a depression in the latter half of the century and competition among producers must have been intense. Knaresborough was at a disadvantage because of its poor access to the major marketing centres – in the case of textiles these were Leeds and York. By specialising in a higher quality linen Knaresborough was able to take advantage of the increase in living standards and fund its higher transport expenses. An industry which began in cottages and small workshops gradually transferred to mills. In 1791 a cotton mill was built on the site of a paper mill on the banks of the River Nidd at Knaresborough, and this was in turn converted to flax spinning in 1811. This was the famous Castle Mill, taken over in 1847 by Walton and Company for both yarn spinning and power-loom weaving. At the beginning of the nineteenth century Knaresborough became famous for its linen. In 1838 Walton and Co., had been appointed linen manufacturers to the Royal Household and in 1851 were awarded the Prince Albert Medal for the completely seamless shirt woven by George Hemshell on a hand loom. Castle Mill has now been converted to private residences. Industrial development was still hampered by the lack of an efficient transport system to bring raw materials and supplies to the town, and to take manufactured goods out to the major trading centres, particularly to the linen market at York. A canal system was proposed around 1818 but deemed to be too expensive due to the large number of locks which would be required. A railway system was costed and proposed in 1820 but did not gain sufficient support and the situation was left unresolved until the middle of the century.

|

|

Dave Teal Knaresborough wills http://www.tealfamily.co.uk/320w.jpg |

The British Mercury Or Annals of History, Politics ..., Volume 12, Issues 1-13

Further wayback

Celtic tribes Brigantes // Carvetii

// Parisii // Corieltauvi // Cornovii // Votadini

Walk

From Spofforth to Bowling... Speculation on Population Impact of the Enclosure Act in Knaresborough Forest area and beyond.

The outline of The Forest of Knaresborough extends far beyond Were Websters butchers for hunting as well as domestic butchering? There was also a Pigot's listing as a "Cattle Dealer" The bishop’s transcript [?1825] (seen at the West Yorkshire Archive Service in Leeds) records that William was a Cattle Dealer [I've seen mention of cattle fairs on given days in market towns] but Piggot’s Directory of professions and trades shows that by 1829 he was the village butcher in Killinghall. Was his later move to Allerton Mauleverer similarly serving domestic & hunting needs?

"Enclosure Acts for small areas had been passed sporadically since the 12th century, but with the rise of the Industrial Revolution, they became more commonplace. In search of better financial returns, landowners looked for more efficient farming techniques.[5] Enclosures were also created so that landowners could charge higher rent to the people working the land. This was at least partially responsible for peasants leaving the countryside to work in the city in industrial factories.[6]" I had always imagined that it was the draw of growing industries that brought the Websters to more industrialized areas. To our 21st century eyes, it is hard to comprehend living in Bradford - described as a dirty and dangerous place where mortality was extraordinarily high and life expectancy plummeted within a couple of decades. ejn

Several selections from the volume below in combination with the Inclosure Laws quote suggest the may have been forced to leave because of a set of circumstances that made it ecnomically impossible to stay. The passages describe a family unit dependent on a combination of economic activities for all the family members that went beyond the profession of the family head -- and several were dependent on having a bit of their own land. ejn If this is the case, it suggests * in the countryside - life-long, multi-generational interdependencies with much of the community, not just their own profession. * relationships in the Spofforth community may have been even stronger than anticipated * If this move was more or less forced, it may have been more traumatic. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Great North Road was the main highway between London and Scotland. It became a coaching route used by mail coaches travelling between London, York and Edinburgh. The modern A1 mainly parallels the route of the Great North Road. Coaching inns, many of which survive, were staging posts providing accommodation, stabling for horses and replacement mounts.[1] Since its origins in pre-Roman times, the Great North Road has been the main north-south thoroughfare of the country and played a part large or small in so much of our history. The legacy of the Roman Road network is still seen in the landscape and road network of today. The Great North Road often follows major Roman routes. Roman roads were surveyed and built from scratch. They connected towns and strategic locations by the most direct possible route. The roads were often paved to permit use in all seasons and weather. Most of the network was complete by 180 AD. Its primary function was to allow the rapid movement of troops and military supplies, but it also provided vital infrastructure for trade and the transport of goods.http://www.great-north-road.org/roman-roads-in-england/ Probably the coffin containing the uncorrupted body of Saint Cuthbert and the head of Saint Aidan was carried up it from Ripon towards its final resting place at Durham a thousand years ago. Edward I carried his queen's body down part of it in 1290, and marked the stops with Eleanor crosses, three of which stood on this road. The catholic rebels in the Pilgrimage of Grace in 1536 used it to march towards the capital. Margaret, daughter of Henry VII, travelled north to marry a Scottish king along it. Butcher Cumberland, fresh from his victory at Culloden, made his triumphant way south down this road. Nearly every monarch of England or of the United Kingdom has ridden, driven or trodden on it and so have most of our statesmen and writers, especially the diarists. As a result there is an abundance of comment and description of most significant places on the route. The Romans built Ermine Street and its continuations to the north as a military road and even after centuries of neglect Harald was able to use it to march his army to York and back in 1066. The Scots used the route to invade England, Warwick the Kingmaker died on it and many of the battles of the Wars of the Roses were fought on and near it. Cromwell's family lived beside it and Monk brought the Coldstream Guards down it during the Civil War. Not least it served as an artery linking many of the RAF stations built on the eastern side of Britain before and during the last war, and many aircraft, before assembly, were carried along it. Walter Scott called it the dullest road in the world, though the most convenient for the traveller, and, while this may be an exaggeration, no one can deny that some of the scenery in the flatlands on the eastern side of England is hardly exciting, especially since they became the grain growing factory that they now are. But there is a romance about the road that Scott himself captured so well in The Heart of Midlothian and which infected even that dour Yorkshireman J B Priestley. Nearly 400 miles separate the capital cities of England and Scotland which stand at either end of the road. The smallest and the largest counties in England are traversed. For most of its length the road runs over low lying land and there are very few hills of any height or length, the highest said to be at Scotch Corner. Stevenage High Street is claimed to be the highest street between London and York. Before new bridges and bypasses were built, there were sharp gradients at several river crossings, such as those at Wentbridge, Durham and Newcastle, which created problems for horses and early motor vehicles. The route through the east of Scotland avoids most of the southern uplands, though the slope up Penmanshiel to Cockburnspath has presented a challenge for travellers through the ages. The heyday of the Road was undoubtedly the era of coaching, which really started when the Royal Mail began to be carried by coach in 1784 but lasted only until the advent of the railway destroyed the coaching trade in the course of about ten years in the 1830s and 40s. There was a second flourish when the motorcar appeared in the early part of the 20th Century. To this day the road remains one of the most highly used and therefore congested routes in the country. The modern road still essentially follows the line taken by ancient travellers, though the width, surface and volume of traffic would astonish anyone from previous times. But still it has a distinction and flavour all of its own. ````````````` =================== The only actual road building ever undertaken in Britain had been done by the Romans. After their legions withdrew from the island, the whole infrastructure of roads, urban centers and country villas was left to wither away through the centuries. Celts, Anglo-Saxons, Vikings and Normans all still had to travel, though, however uncomfortable and cumbersome their progress across the countryside might be. By the time Boswell and Dr. Johnson traveled the Great North Road in the late 18th century, improvements were well underway on both the road and the means of travel upon it. It must have seemed state-of-the-art luxury, indeed, to traverse roads that were somewhat graded and maintained by recently established local “turnpike trusts,” which often financed the work with user fees that were collected at toll booths. Sprung stagecoaches now plied the road on regular routes and fixed schedules—a considerable improvement over the plodding wagons of bygone years. Along the route of the Great North Road the infrastructure of travel evolved, with inns and public houses growing up along the way as surely as fast food franchises and lodging chains mark the popular paths of road travel today. Travel time from London to Edinburgh was cut from 12 days to four in the 18th century. What adventures would I find today, I wondered, during four days on the Great North Road? A picturesque history of Yorkshire: being an account of the ..., Volume 2By Joseph Smith Fletcher |

Below are quotes from a volume on the woolen industry in Yorkshire. The prevalence of the industry -- over centuries -- |

Very early Yorkshire mentions of Webster and Walker. Over centuries wool work moved to be more centralized - mostly east and later more decentralized in west with home producers who added it to their other family based industries - a small few acres of land , perhaps trees. cows and swine. Some beef and pork would have been salted for late 1580s era The male employment was "strongly supplemented by the employment of women and children. In 1588, one loom consumed the yarn carded and spun by five or six persons, and most of the work of preparing yarn for the weaver was performed by women and young persons. Every cottage had its spinningwheel or distaff, as an almost essential part of the domestic equipment. The clothier sent his wool out to the spinners, who, in their homes, spun the mass of raw material into fibre ready A third point of interest lies in the comparison of the rates paid to industry and agriculture. The most important maxima fixed in the 1647 assessment were : Agriculture. Maximum Wages. Bailiffs or foremen hired by gentlemen or wealthy persons per annum . . . . 3 los - od. 1 Chief servants in the employ of ordinary yeomen or husbandmen . . . . . 3 os - dFemale servants ....... 25s. to 30s. Mowers of grass and corn, per day, with or without food ........ $d. or lad. Ordinary farm labourers, per day, with or without \ Summer, 3d. or 6d. food ........ \ Winter, 2d. or 5^. Building Trades. Master masons and carpenters .... (id. or \zd. to p 150 file:///C:/Users/User/Documents/1-websites/genealogy/Yorkshire-woollen-worsted-earliest%20times-indus-rev.pdf Walkers (fullers) p.22 The Bradford mill, for instance, was let in the early 'forties to William and James Walker, at a rental of ten shillings per annum.2 In 1346 James resigned his share of the mill to

William, being

' unable to hold the said mill on account of

poverty '. ' new rent ' for the term of the father's life, being promised in return ' that there shall no strange fuller enter within the town and liberty of the Court of the Lord of Bradford, . . . neither shall anything be taken or carried out of the said town to be worked upon, nor shall any one use that craft in the said town, except (the Walkers) and their servants '. 6,,, In some wills we get a glimpse of another side of the clothier's life, as for example, in that of John Walker of Armley, clothier (1588; : ... p 169 great hurt of the merchants and inhabitants of this town '.* These West Riding merchants generally sprang from local families of clothiers. The father would be a clothier, probably on a rather large scale of business, selling his cloths in the market at Leeds, or at Blackwell Hall and Bartholomew Fair. Thanks to the father's energies and thrift, the son was able to become apprenticed to some merchant, and in time set up as a fully qualified merchant and member of the trading companies, taking the wares of the West Riding to foreign parts. One instance of this is seen in the rise of the Denisons, a family prominent in the history of Leeds. George Denison, born in 1626, lived at Woodhouse, and engaged in the occupation of a clothier. His son, Thomas, became a merchant and member of the Merchant Adventurers ; Thomas's son in time followed the same career, and was elected Mayor of Leeds in 1727 and 1731. 2 Other branches of the family had a similar history. The Denison family had its origins in clothiers' cottages. Its members afterwards numbered three knights, a baron, a viscount, a Speaker of the House of Commons, a judge, a colonial governor, and a bishop, not to mention Mayors of Leeds and lesser dignitaries. The history of other families is largely a repetition of the above story ; and this line of development accounts in part at least for the rise of the Armitagcs, the Jacksons, the Metcalfes, the Walkers, the Wades, and other families which have played a large part in the economic and political life of Leeds. "...many witnesses in 1638 agreed that the kerseys, although now made of inferior wool, were ' both finer, better made, and of greater value and price than the said kersies were ' a quarter of a century before. 2 Thus, on the whole, Yorkshire kerseys had increased in variety, in length, in quality, and in value. And yet they were only paying a penny each for subsidy and ulnage ! This was bound, sooner or later, to bring about another conflict between the clothiers and those interested in the collection of the cloth fees, and the legal battle took up the years 1637 8. At this time the control of the ulnage for the West Riding was in the hands of Thomas Metcalfe of Leeds, 1 Evidence of Wm. Busfield of Leeds ; Exch. Dep. by Comm., 14 Chas. I, Mich., no. 20, York. 2 In 161 3, average price for Halifax kersey is. $d. to 2s. per yard. In 1638 the cheapest valued at is. iod. ; others sold at 25. bd. to 4s. 6d. per yard. Even Kcighley kerseys, 18 yards in length, sold at 25. to 2s. 6d. per yard. Higher still in the industrial scale came the really big clothiers who were to be found in many parts, especially around Leeds, during the latter half of the eighteenth century. These men were large employers, and, in the congregation of workpeople in their shops, they established miniature factories many years ,/ before the perfection of the power loom or the application of steam. For instance, James Walker of Wortley employed twenty-one looms, of which eleven were in his own loom-shop, and the remainder erected in the houses of his weavers. 2 L. Atkinson, of Huddersfield, had seventeen looms in one room, and also employed weavers who worked in their own abodes. 3 These looms were all worked by hand, and in addition to the men engaged in weaving there were many women and children busy preparing yarn. Thus we see that there was no standard size of master clothier. He might be of any status, from the small man, employing his own family and one or two outsiders, to the wealthy clothier, with his two-score looms and his half a hundred workpeople. been cast, to-day over his dreary toil. Such were the advantages from the workman's point of view, and many masters were quite willing to let the work be done in the men's homes rather than in their own shops. The weavers were paid at the same piece rate whether they were home workers or not, but masters felt that, human nature being what it was, it might be desirable to have one's employees under direct supervision. Thus in 1806 Mr. Walker, of Wortley, explained that he had his men working together as much as possible, ' on purpose to have [the work] near at hand, and to have it under our inspection every day, that we may see it spun to a proper p 5 At Leeds x in 1201 a certain Simon the Dyer was fined 100s. for selling wine contrary to the legal assize ; 2 the nature of the entry and the amount of the payment indicate that Simon engaged in other trades besides that of dyeing, and was a wealthy man. Robertus Tynctor (dyer) de Ledes 3 was a witness to a Kirkstall Abbey charter not later than 1237, and an inquisition of 1258 records the names of William Webster (textor), Richard and Andrew Taillur (tailors ?), and John Lister (tinctor), in the list of Leeds cottars. 4 A little later, in 1275, Alexander Fuller of Leeds was fined for making cloth which was not of the

proper breadth, ================ Richard Webster Sheffield 1669 http://www.pennineheritage.org.uk/pennine-trails/sam-hill Proto-industrialisation: recherches récentes et nouvelles perspectives ...edited by René Leboutte |

Perhaps their move from Spofforth was influenced by activities resulting from inclosure/enclosure acts. Some information regarding Follifoot - just 2 miles NW of Spofforth. " At the centre of the parish lies the Rudding Park Estate, with its' Regency House and Parkland, once the home to the Radcliffe family. The village is not listed in the Doomsday Book and the earliest documentary evidence of the village occurs in the 12th century in land and tax documents. In 1186 it is recorded that Nicolas, son of Hugh, son of Hippolitus de Braam gave one "toft" - a field where a house or building stood, in Folyfait, to Gilbert, son of Thomas Oysel de Plumpton. Gilbert then donated this property to Fountains Abbey. In 1203, Henriicus, Parson of Knaresborough, was fined in a York court for some illegality concerning lands at Folifeit. When Kirkby's Inquest was made in 1284, it was noted that a fourth part of Follifoot was held by William de Hartlington, owner of the Manor of Braham, and in 1364, Edward III appointed Thomas de Spaigne custodian of "one Messuage" - a dwelling house - and forty acres of land in Follifoot. Indeed by the time of Richard III the village was large enough to be marked on a 1378 map and for the villagers to be dunned for a substantial sum in poll taxes. ...IN the early part of the reign of James I, Richard Paver of Braham Hall obtained the lease of the Follifoot lands from the King for £140.3.4d. These were the lands which had belonged to the Priory of Newburgh before the Dissolution of the Monastries. The lands were held of the Manor of East Greenwich in free socage for the annual rent of £4.7.6d. for the Follifoot lands and £2.15.8d. for the Aketon lands. ...The establishment of Rudding Park is of relatively recent date, 19th century, and until this time Follifoot had no Manor House as such. The Manorial rights to the village were held by the lords of the Manor of Spofforth, namely the Percys, Earls of Northumberland and the Egremonts, Earls of Sussex. During the 18th century, at the time of the Enclosure Acts, Follifoot was the scene of an attempted "land grab". The establishment of Manorial rights was particularly important at this time, as the soil royalties of the moor and common lands were the prerogative of the Lord of the Manor. Daniel Lascelles, who had just purchased the Manor of Plumpton from Robert Plumpton's estate for £28,000, had also obtained land and cottages in Follifoot from a Dr. Hodgson for £1,000. He then continued the practice, illegally adopted by the Doctor, of holding a "Manor court". ... The area of the land in dispute was estimated at 1,100 acres, and eventually 1/16th of this was offered to Mr. Lascelles in compensation for waiving his claim to the Manor. Documents produced by George, Lord Egremont to establish that Follifoot was part of his Manor of Spofforth included court rolls from the times of Edward IV, Henry VI, Henry VII, Henry VIII, Elizabeth I, James I, Charles I and Charles II. The reports of the village constables to the Manorial court at Spofforth were also produced. The Book of the Survey of the Manor of Spofforth compiled in 1577 also listed Follifoot and Aketon in the Manor of Spofforth, with the primary landowners listed as William Plumpton, the Priory of Newburgh (who has held land in Follifoot at least since 1315), and Perivale Tombington. Alice Jonson was named as a tenant holder. It is interesting to note that the executors of the will of Thomas Richardson of Knaresborough, purchased a pice of land in Follifoot in 1785, the income from which was used to supplement the income of the Petty School established by Richardson on Pump Hill, Knaresborough. This transaction is recorded on a stone slab to be seen at the present time over the doorway of the old school, now a private house. |

|

Collectio rerum ecclesiasticarum de Dioecesi Eboracensi, or, collections ...Webster Surname Meaning & Statistics (forbearers)3,214th most common surname in the worldApproximately 168,994 people bear this surnameMost prevalent in: United StatesHighest density in: Anguilla

|

Here are the spice containers from the spice box that I believe belonged to Maggie Calam Webster. This might give an idea of the baking spices important to them at the time. |

| Websters Cambridge |

Websters certainly grew up with tales of Robin Hood, but Robin was not always considered to be so heroic. Robin Hood is a heroic outlaw in English folklore who, according to legend, was a highly skilled archer and swordsman. Traditionally depicted as being dressed in Lincoln green,[1] he is often portrayed as "robbing from the rich and giving to the poor"[2][3] alongside his band of Merry Men. Robin Hood became a popular folk figure in the late-medieval period, and continues to be widely represented in literature, films and television. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robin_Hood#Robin_Hood_of_Wakefield YorkshireNottinghamshire's claim to Robin Hood's heritage is disputed, with Yorkists staking a claim to the outlaw. In demonstrating Yorkshire's Robin Hood heritage, the historian J. C. Holt drew attention to the fact that although Sherwood Forest is mentioned in Robin Hood and the Monk, there is little information about the topography of the region, and thus suggested that Robin Hood was drawn to Nottinghamshire through his interactions with the city's sheriff.[99] And, the linguist Lister Matheson has observed that the language of the Gest of Robyn Hode is written in a definite northern dialect, probably that of Yorkshire.[100] In consequence, it seems probable that the Robin Hood legend actually originates from the county of Yorkshire. Robin Hood's Yorkshire origins are universally accepted by professional historians.[101] Barnsdale

Blue Plaque commemorating Wentbridge's Robin Hood connections

A tradition dating back at least to the end of the 16th century gives Robin Hood's birthplace as Loxley, Sheffield, in South Yorkshire. The original Robin Hood ballads, which originate from the fifteenth century, set events in the medieval forest of Barnsdale. Barnsdale was a wooded area covering an expanse of no more than thirty square miles, ranging six miles from north to south, with the River Went at Wentbridge near Pontefract forming its northern boundary and the villages of Skelbrooke and Hampole forming the southernmost region. From east to west the forest extended about five miles, from Askern on the east to Badsworth in the west.[102] At the northern most edge of the forest of Barnsdale, in the heart of the Went Valley, resides the village of Wentbridge. Wentbridge is a village in the City of Wakefield district of West Yorkshire, England. It lies around 3 miles (5 km) southeast of its nearest township of size, Pontefract, close to the A1 road. During the medieval age Wentbridge was sometimes locally referred to by the name of Barnsdale because it was the predominant settlement in the forest.[103] Wentbridge is mentioned in an early Robin Hood ballad, entitled, Robin Hood and the Potter, which reads, "Y mete hem bot at Went breg,' syde Lyttyl John". And, while Wentbridge is not directly named in A Gest of Robyn Hode, the poem does appear to make a cryptic reference to the locality by depicting a poor knight explaining to Robin Hood that he 'went at a bridge' where there was wrestling'.[104] A commemorative Blue Plaque has been placed on the bridge that crosses the River Went by Wakefield City Council. The Saylis

|

What image of Knights Templar did our Websters have? Knights Templar (Freemasonry) Modern wikipediaThe Knights Templar, full name The United Religious, Military and Masonic Orders of the Temple and of St John of Jerusalem, Palestine, Rhodes and Malta, is a fraternal order affiliated with Freemasonry. Unlike the initial degrees conferred in a regular Masonic Lodge, which only require a belief in a Supreme Being regardless of religious affiliation, the Knights Templar is one of several additional Masonic Orders in which membership is open only to Freemasons who profess a belief in Christianity. One of the obligations entrants to the order are required to declare is to protect and defend the Christian faith. The word "United" in its full title indicates that more than one historical tradition and more than one actual order are jointly controlled within this system. The individual orders 'united' within this system are principally the Knights of the Temple (Knights Templar), the Knights of Malta, the Knights of St Paul, and only within the York Rite, the Knights of the Red Cross. the Masonic order of Knights Templar derives its name from the medieval Catholic military order Knights Templar. However, it does not claim any direct lineal descent from the original Templar order. The earliest documented link between Freemasonry and the Crusades is the 1737 oration of the Chevalier Ramsay. This claimed that European Freemasonry came about from an interaction between crusader masons and the Knights Hospitaller.[1] This is repeated in the earliest known "Moderns" ritual, the Berne manuscript, written in French between 1740 and 1744.[2] Medieval Knights Templar [Catholic military order] The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon (Latin: Pauperes commilitones Christi Templique Salomonici), also known as the Order of Solomon's Temple (French: Ordre du Temple or Templiers, Arabic: فرسان الهيكل), the Knights Templar, or simply as Templars, was a Christian military order recognised in 1139 by papal bull Omne Datum Optimum of the Holy See.[4] The order was founded in 1119 and active from about 1129 to 1312.[5] The order, which was among the wealthiest and most powerful, became a favoured charity throughout Christendom and grew rapidly in membership and power. They were prominent in Christian finance. Templar knights, in their distinctive white mantles with a red cross, were among the most skilled fighting units of the Crusades.[6] Non-combatant members of the order managed a large economic infrastructure throughout Christendom,[7] developing innovative financial techniques that were an early form of banking,[8][9] and building fortifications across Europe and the Holy Land. The Templars were closely tied to the Crusades; when the Holy Land was lost, support for the order faded. Rumours about the Templars' secret initiation ceremony created distrust, and King Philip IV of France – deeply in debt to the order – took advantage of the situation to gain control over them. In 1307, he had many of the order's members in France arrested, tortured into giving false confessions, and burned at the stake.[10] Pope Clement V disbanded the order in 1312 under pressure from King Philip. The abrupt reduction in power of a significant group in European society gave rise to speculation, legend, and legacy through the ages. The re-use of their name for later organizations has kept the name "Templar" alive to the modern day. The teachings and traditions of Freemasonry are essentially comprised of symbolism, allegory and metaphor inspired by the ancient construction of the Temple of Solomon, which is applied as an esoteric representation for principles of personal transformation. Additionally, the concept of stonemasonry itself is considered symbolic of an intended stewardship role as “architects of society”. This is related to the predominant Masonic requirement of belief in the Supreme Being (i.e. God), referred to by the symbolic title “Great Architect of the Universe”. The use of ceremonial regalia in Freemasonry began as a new practice contemporary with its creation in the 15th century [1], with regalia serving as an additional dimension of symbolism supporting the esoteric teachings. The famous system of “degrees” of Freemasonry originated from the secular tradition of medieval craft Guilds, since the Guilds regulated the qualifications of all stone masons. Due to this professional regulatory context, Masonry developed independently as a network of Lodges. Each national or regional Grand Lodge is autonomous from those of other countries, Lodges of different jurisdictions do not necessarily recognize each other [2], and there is no single international governing body [3]. The Masonic tradition of sworn secrecy came from the legitimate quasi-legal “trade secret” needs of the professional craft Guilds of stone masons in the 15th century. Although modern Freemasonry no longer involves any trade craft requiring such protection, that practice is still valid for the sake of tradition. Indeed, that early legal doctrine of protecting “trade secrets” remains an important part of international intellectual property law to this day.... In contrast, the chivalric Templar Order focuses on the total body of knowledge gained from its nine years of deep underground archaeological excavation of the actual Temple of Solomon from 1118 AD, including an accumulated library of the Essenes discovered within that Temple. The 12th century Templars attributed their famous stone work and building skills to their reverse engineering from that ancient site, supported by mentoring from Egyptian chivalric and priestly Orders. ‘The Structure of Freemasonry’ in Life Magazine (08 October 1956) in The Masonic Library & Museum of Pennsylvania, featuring Knights Templar at 33rd Degree Knights Templar in YorkshireBy Diane Holloway, Trish Colton, Dr. Evelyn Lord The History Press, Oct 24, 2011 Ribston, North Yorkshiremap ref SE 392 538 William de Grafton was named as the Preceptor of Ribston at the suppression, he also served as the Preceptor of Yorkshire a position thought to be unique to the county. After his trial by inquisition at York he was sent to Selby Abbey to undertake one year of Penance, years later something strange occurred, he was given secular release by the Master of the Temple, (This document apparently survives and sets a puzzle as it is dated 1331, long after the official suppression). Below is a translation from the original Latin of part of the document as described in "The History of Temple Newsam" by Weater 1889 Edition page 97 it reads:- "The Master of the Temple with the assent of his brethren absolves from his vow William de Grafton one of the brethren of the Order and granted that having laid aside the habit of the Temple he may be allowed to turn himself to the secular state which King Edward II and the present King have confirmed". Though most of the of the Preceptory complex has long since disappeared, the original Templar chapel still exists and is incorporated into the end of the present Ribston Hall, this unfortunately is a private residence so access is restricted. Some of the surrounding Templar Churches still exist and the Church of St Andrew in Ribston village has a pair of Knightly effigies either side of the alter that are supposed Templars. Interestingly the Church of nearby Spofforth has two stones "hidden" in its outer walls, one high up above the North aisle roof the other near ground level at the East end, these stones are a totally different composition to the stone used on the rest of the Church, a glance at the accompanying picture of the East one saves a thousand words. On the trail of the Templars LeedsIvanhoeIn the 19th century there was a vogue for historical novels. Sir Walter Scott's Ivanhoe, featuring the Templars as the villains, was a huge success. Ivanhoe features a preceptory called Temple Stowe. There was no Templar estate with this name, but many people believe the novel was using Temple Newsam under a different name. There is a clock in the Thornton's Arcade in Leeds city centre which features a scene from Ivanhoe and some modern places in Leeds may carry the name of Temple Stowe (such as Templestowe Crescent). History of St James From ancient times…Wetherby was originally part of the ancient parish of Spofforth. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/yorks/vol3/pp256-260 HOUSES OF KNIGHTS TEMPLARS67. THE PRECEPTORY OF YORKSHIREThe Order of Knights of the Temple of Jerusalem was founded in 1119, but it was not until the middle of the 12th century that they began to acquire possessions in Yorkshire, where they eventually established at least ten preceptories. Their prosperity was brought to an abrupt close early in the 14th century; in 1308 Sir John Crepping, Sheriff of Yorkshire, received the king's writ to arrest the Templars within the county and sequester all their property. (fn. 1) Twenty-five Templars were placed in custody in York Castle and examined on the charge or heresy, idolatry, and other crimes, brought against the order by Pope Clement V and Philip IV of France. After a long-drawn-out trial, in which the evidence adduced against the knights was too flimsy to secure the desired conviction, a compromise was arrived at by which the brethren, without admitting their guilt, acknowledged that their order was strongly suspected of heresy and other charges from which they could not clear themselves. They then received absolution at the hands of the Bishop of Whithern on 29 July 1311, were released from prison, and were distributed amongst the various monasteries. (fn. 2) Next year the suppression of the order was decreed by the pope, and a large portion or their estates was made over to the order of the Knights Hospitallers. The Yorkshire estates of the Templars consisted of the preceptories of Copmanthorpe (with the Castle Mills of York), Faxfleet, Foulbridge, Penhill, Ribston, Temple Cowton, Temple Hirst, Temple Newsam, Westerdale, and Whitley, and the manors of Alverthorpe and Etton, which, although possessing chapels, do not seem to have had preceptors. All these estates, with the exception of Faxfleet, Temple Hirst, and Temple Newsam, passed to the Hospitallers. So important were the Templars' holdings in the county that a ' chief preceptor' or ' master' was appointed for Yorkshire from early times. Chief Preceptors of YorkshireWalter Brito, c. 1220 (fn. 3) Roger de Scamelesbi, c. 1240 (fn. 4) William de Merden, c. 1270 (fn. 5) Robert de Haleghton, or Halton, occurs 1290, 1293 (fn. 6) Thomas de Thoulouse, c. 1301 (fn. 7) ¶William de Grafton, occurs 1304, (fn. 8) arrested 1308 (fn. 9) 72. THE PRECEPTORY OF RIBSTON AND WETHERBY About 1217 Robert de Ros gave to the Templars his manor of Ribston, with the advowson of the church, the vill and mills of Walshford, and the vill of Hunsingore. (fn. 35) This property had come to Robert de Ros from his mother, Rose Trussebut; and her sisters, Hilary and Agatha, at some date prior to 1240, made grants of various woods in the neighbourhood to the preceptory. Robert son of William Denby gave the vill of Wetherby to the Templars, and other smaller grants followed. Besides the church of Hunsingore the Templars had chapels at Wetherby, Ribston, and apparently at Walshford. The chapel of St. Andrew at Ribston stood in the churchyard of the parish church, and in 1231 was the subject of an arrangement between the brethren and the rector. About this time a sum of £2 16s. was assigned for the support of a chaplain at Ribston for the good of the soul of Robert de Ros. The estates at Ribston and Wetherby seem to have formed a single preceptory, but were valued separately at the time of their seizure in 1308. Wetherby (fn. 36) was then returned as worth £120 7s. 8d., and Ribston, including North Deighton and Lound, at £267 13s. (fn. 37) The chapels in each case were simply furnished, but Ribston was remarkable as possessing two silver cups, three masers, and ten silver spoons—more secular plate than all the other Yorkshire preceptories put together. At the time of the trial of the Templars, Gasper de Nafferton, who had been chaplain at Ribston, related certain cases in which the brethren had observed a great and, as he now perceived, suspicious secrecy in matters touching admission to the order. (fn. 38) And Robert de Oteringham, a Friar Minor, who gave evidence against the Templars, (fn. 39) said that at Ribston a chaplain of the order, after returning thanks, denounced his brethren, saying ' The Devil shall burn you!' He also saw one of the brethren, apparently during the confusion which ensued on this exclamation, turn his back upon the altar. Further, some twenty years before, he was at Wetherby, and the chief preceptor, who was also there, did not come to supper because he was preparing certain relics which he had brought from the Holy Land; thinking he heard a noise in the chapel during the night, Robert looked through the keyhole, and saw a great light, but when he asked one of the brethren about it next day he was bidden to hold his tongue as he valued his life. At Ribston, also, he once saw a crucifix lying as if thrown down on the altar, and when he was going to stand it up he was told to leave it alone. As this was some of the most direct and damaging evidence given during the trial the weakness of the case against the Templars is obvious. Of the preceptors only two names appear to have survived. William de Garewyz was preceptor of Wetherby in, or a little before, 1293, (fn. 40) and Richard de Keswik, or Chesewyk, who was admitted to the order at Faxfleet in 1290, (fn. 41) became preceptor of Ribston about 1298 (fn. 42) and still held that post in 1308 when he was arrested, with Richard de Brakearp, claviger, and Henry de Craven, a brother in residence at Ribston. (fn. 43) http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/yorks/vol3/pp256-260#h3-0008 Houses of Knights TemplarPages 256-260 A History of the County of York: Volume 3. Originally published by Victoria County History, London, 1974. This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved. |